At the Waycross Seven Out Superfund Site meeting, caller Anthony Samsel said (42 minutes and 10 seconds into the video) of a site in Massachusetts:

I was the first person to track contamination of the ground to aquifers that travel several miles; plastics, formaldehyde, from a plastics manufacturing plant, and there was contamination of city wells with a lot of cancer clusters and a lot of sick, dead, and dying people.

He was talking about the Wells G & H Superfund Site in Woburn, MA, where, according to EPA,

The groundwater was contaminated with industrial solvents, called volatile organic compounds (VOCs), such as trichloroethylene (TCE) and tetrachloroethylene (PCE). Soil on the five properties was contaminated with VOCs, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and pesticides. Sediments in the Aberjona River were contaminated with PAHs and heavy metals such as chromium, zinc, mercury and arsenic.

Thirty years later, that one is still toxic.

In a 29 September 2011 coment Samsel said he first raised a red flag about TCE (Trichloroethylene solvent) in Woburn in the 1970s. The context is the EPA releasing 28 Sepember 2011 a final health assessment for TCE:

The final assessment characterizes the chemical as carcinogenic to humans and as a human noncancer health hazard.

Samsel said he was researching

a Georgia-Pacific plant in Arkansas

and

warned of the Georgia-Pacific plant just south of Waycross.

He noted some of the waste from that plant was sent to the Seven Out site.

Samsel said he was researching

a Georgia-Pacific plant in Arkansas

and

warned of the Georgia-Pacific plant just south of Waycross.

He noted some of the waste from that plant was sent to the Seven Out site.

And where-ever they start, he said,

These contaminants can travel miles.

This is a point corroborated both by the Woburn case and by for example the Fort Gillem case in Clayton County, Georgia.

Somebody wanted to know how long would it take to fix this, for resolution? Answer from Anthony Samsel: it depends on the specific chemicals. Clarification: it depends on the extent of contamination, and first need to establish the plume of contamination.

From what Samsel could see from what the Superfund did, they were concerned with emptying the tanks, not with contamination of groundwater, wells, or soils. They only looked at the site, not farther.

And that was very very irresponsible of them….If contaminated with PAHes, they’re not going to go away. The property values essentially with these chemicals in the soil are worth nothing. The city should not even be collecting taxes on them.

In other words, there is no cure beyond abandoning the affected areas. And even that doesn’t solve the problem, because:

These materials continue to move.

Joan McNeal talked about replacing the soil and pumping the water up out of the ground. I don’t think she quite got the gist: once it’s in the aquifer, there’s really no way to clean it up, and it continues to spread.

So what many people in Waycross really need would appear to be

a way to get out of their now-unsellable property.

Funding for buyouts, in other words.

Which only happened for Love Canal

after activists held EPA representatives hostage in 1980.

And even then a new administration’s EPA head

refused to continue buyouts.

You do remember Love Canal?

The Niagara Falls, New York neighborhood built on a site

used to bury toxic waste?

The famous case that helped cause the creation of the Superfund program,

together with regulations that were supposed to prevent Love Canal from

ever happening again?

Well, it’s happened again, this time in Waycross, Georgia.

So it’s time for more buyouts.

after activists held EPA representatives hostage in 1980.

And even then a new administration’s EPA head

refused to continue buyouts.

You do remember Love Canal?

The Niagara Falls, New York neighborhood built on a site

used to bury toxic waste?

The famous case that helped cause the creation of the Superfund program,

together with regulations that were supposed to prevent Love Canal from

ever happening again?

Well, it’s happened again, this time in Waycross, Georgia.

So it’s time for more buyouts.

Lois Gibbs of Love Canal activism fame in 1981 founded the Center for Health, Environment & Justice,

CHEJ mentors and empowers community-based groups to become effective in achieving their goals and build a national environmental health and justice movement where every community is safe to live, work, pray and play without toxic hazards.

Waycross activists might want to contact CHEJ.

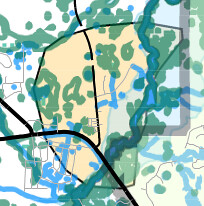

And maybe we should think about aquifer contamination before

planting a subdivision on top of an aquifer recharge zone

or

locating more toxic chemical plants in Lowndes County.

Maybe we should find out

what’s already in the landfill

on top of an aquifer recharge zone

and a little bit uphill from the Withlacoochee River

in Lowndes County, Georgia.

And maybe we should think about aquifer contamination before

planting a subdivision on top of an aquifer recharge zone

or

locating more toxic chemical plants in Lowndes County.

Maybe we should find out

what’s already in the landfill

on top of an aquifer recharge zone

and a little bit uphill from the Withlacoochee River

in Lowndes County, Georgia.

-jsq

Short Link:

Pingback: Waste from Superfund site in Waycross went to Lowndes County landfill | On the LAKE front