Maureen Downey blogged for AJC 5 October 2011, Forget school vouchers. The route to improving education may be housing vouchers.

I’d say that’s a bad solution to the problem the study identifies, and we already know better solutions. But first, from the abstract of the the study (Neighborhood Effects in Temporal Perspective: The Impact of Long-Term Exposure to Concentrated Disadvantage on High School Graduation, by Geoffrey T. Wodtkea, David J. Harding, and Felix Elwert, in American Sociological Review October 2011 vol. 76 no. 5 713-736):School voucher proponents argue that kids need a way out of failing schools, but research increasingly suggests that it would be more effective to provide them a way out of failing neighborhoods.

Should we consider giving poor families in low-performing school zones housing vouchers that they could use to relocate in the zone of a school performing above the area median?

We find that sustained exposure to disadvantaged neighborhoods has a severe impact on high school graduation that is considerably larger than effects reported in prior research. We estimate that growing up in the most (compared to the least) disadvantaged quintile of neighborhoods reduces the probability of graduation from 96 to 76 percent for black children, and from 95 to 87 percent for nonblack children.Could bussing those same children to school during the day, only to return them to the same neighborhoods at night, really overcome that much difference? The study doesn’t address that question, but proponents of “unification” should.

And now the older study:

Supporters of housing vouchers often cite Chicago’s Gautreaux program, which grew out of a 1976 consent decree in a lawsuit over discriminatory housing practices by the local housing authority and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The suit argued that public housing deliberately had been built in ghettos so as to avoid economic and racial integration. The consent decree required the housing authority to subsidize apartments in the suburbs for qualifying low-income families willing to move, with the stipulation that similarly poor families not exceed a certain proportion in any one area.We all already knew living in the ghetto was a problem; even Elvis knew that; but maybe we didn’t know how much of a problem.Between 1976 to 1998, more than 7,000 families participated, with more than half moving to suburbs, providing a basis to examine the benefits of economic integration. Children of families that decamped to the suburbs had higher academic achievement, lower dropout and higher college attendance rates than peers who stayed in the ghetto. The parents also fared better, with mothers more likely to be employed at a living wage and less likely to return to welfare. The conclusion: Neighborhoods matter more than anyone expected.

What do the researchers of the new study consider a disadvantaged neighborhood?

For the study, the researchers defined disadvantaged neighborhoods as those characterized by high poverty, unemployment, and welfare receipt; many female-headed households; and few well-educated adults. “Our results indicate that sustained exposure to disadvantaged neighborhoods has a much greater negative impact on the chances a child will graduate from high school than earlier research has suggested,” says Wodtke.How about if we address those characteristic problems?

Moving selected children and families out of bad neighborhoods

may be good for those lucky few, like the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

But what about the ones who get stuck back in the ghetto?

And what if you move everyone out, what happens to the disaster

zone you leave behind?

Plus, where do you move them to?

Newly-built subdivisions in the country, destroying agricultural

land, increasing flooding, and requring paying for bussing that

costs more than any tax income advantage to the school systems?

Moving selected children and families out of bad neighborhoods

may be good for those lucky few, like the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

But what about the ones who get stuck back in the ghetto?

And what if you move everyone out, what happens to the disaster

zone you leave behind?

Plus, where do you move them to?

Newly-built subdivisions in the country, destroying agricultural

land, increasing flooding, and requring paying for bussing that

costs more than any tax income advantage to the school systems?

How about instead we address those underlying problems?

Poverty is the root problem.

Moving people to subdivisions still doesn’t give them jobs.

As a start, how about we get on with solar energy and retrofitting houses

Poverty is the root problem.

Moving people to subdivisions still doesn’t give them jobs.

As a start, how about we get on with solar energy and retrofitting houses

for efficiency and conservation so people in those neighborhoods

can have jobs doing that and can reduce their bills at the same time?

How about we find ways to locate new facilities like libraries

and auditoriums in those “bad” neighborhoods to make them better?

We could find a way if we wanted to.

That sounds like a job for… the Chamber of Commerce!

for efficiency and conservation so people in those neighborhoods

can have jobs doing that and can reduce their bills at the same time?

How about we find ways to locate new facilities like libraries

and auditoriums in those “bad” neighborhoods to make them better?

We could find a way if we wanted to.

That sounds like a job for… the Chamber of Commerce!

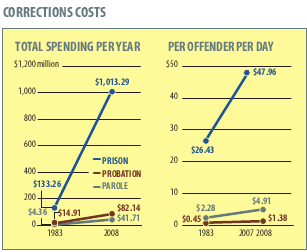

Another huge problem is incarceration.

With 1 in 13 Georgia adults in jail, prison, probation, or parole,

and two thirds of them being black, and by far most of them male,

it’s no wonder there are so many female-headed households, or so many

with poverty, unemployment, or on welfare.

Let’s stop the Industrial Authority from locating a private prison here,

With 1 in 13 Georgia adults in jail, prison, probation, or parole,

and two thirds of them being black, and by far most of them male,

it’s no wonder there are so many female-headed households, or so many

with poverty, unemployment, or on welfare.

Let’s stop the Industrial Authority from locating a private prison here,

and let’s end the School to Prison Pipeline, just for starters.

Then let’s

end the failed War on Drugs:

that alone will empty the prisons of most of their prisoners.

and let’s end the School to Prison Pipeline, just for starters.

Then let’s

end the failed War on Drugs:

that alone will empty the prisons of most of their prisoners.

You may not agree with everything I suggest, but I suspect many of you, gentle readers, will agree that many of those suggestions make more sense than school “unification” or consolidation, which would only make matters worse.

How about if we address those problems instead of wasting time

and effort on a failed non-solution from forty years ago?

Vote No November 8th, for the children,

for our neighbors, for ourselves, for our community.

-jsq

Short Link: