The UGA Center for Agribusiness and Economic Development has

quantified the economic effects of eating local food in Georgia,

in this report:

The Local Food Impact: What if Georgians Ate Georgia Produce?

Prepared by: Sharon P. Kane, Kent Wolfe, Marcia Jones, and John McKissick Center Report: CR-10-03 May 2010

The UGA Center for Agribusiness and Economic Development has

quantified the economic effects of eating local food in Georgia,

in this report:

The Local Food Impact: What if Georgians Ate Georgia Produce?

Prepared by: Sharon P. Kane, Kent Wolfe, Marcia Jones, and John McKissick Center Report: CR-10-03 May 2010

If Georgians produced all of the fruits and vegetables that they consumed, it could provide a way to close this utilization gap (the difference between state-wide production and consumption) of over $780 million per year. Even if this level can’t be achieved, simply closing the gap in one commoditylettuce, for examplecould mean an additional $83.6 million of direct revenue to local producers.

What is the lettuce gap? The Cordele Dispatch explains it:

They found, for example, the average Georgian eats about 30 pounds of fresh lettuce per year, or about 285 million pounds state-wide.Yet the state produces less than 245,000 pounds per year, which is less than one-tenth of one percent of the amount of lettuce that Georgians consume. Closing that gap would generate an additional $83.6 million in lettuce sales.

And that’s not the only gap:

Similarly, there are major gaps for other produce, including a $228 million gap for apples, a $62 million gap for bell peppers, a $46 million gap for a broccoli, a $12.8 million gap for carrots, …, a $235 million gap for tomatoes….

How to close those gaps? Here’s one way:

If Georgia vegetable, melon, fruit, and nut farms increased their direct-to-consumer sales per farm to the same average dollar value per farm as reported nationally, the result would be an increase from $7 million in direct sales to over $13 million. This increase of direct sales, when including linkages throughout the economy, would contribute 232 jobs, $7.4 million in labor income, $10.7 million in value added, and $23.6 million in output to the Georgia economy.

What are direct-to-consumer sales?

….methods such as Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), farmer’s markets, roadside stands, or pickyour-own.Tasty, too. I thought I didn’t like strawberries until I tried some from the you-pick-’em on Bemiss Road near Moody AFB.

Such sales work even for foods that Georgia produces more than it consumes, such as blueberries, lima beans, onions, pecans, and watermelons. Farmers get more profit by selling directly.

Georgia will always have a gap for some foods,

just as it will always have a surplus for some foods.

Few states can grow as many pecans as Georgia,

and Vidalia onions are branded like Champagne,

so that they’re not real unless they’re grown

in certain counties of Georgia.

Georgia may never grow as many apples as Georgians eat,

and is unlikely to become a big producer of cranberries.

But surely we can close the gap in okra, peaches, and pumpkins!

Georgia will always have a gap for some foods,

just as it will always have a surplus for some foods.

Few states can grow as many pecans as Georgia,

and Vidalia onions are branded like Champagne,

so that they’re not real unless they’re grown

in certain counties of Georgia.

Georgia may never grow as many apples as Georgians eat,

and is unlikely to become a big producer of cranberries.

But surely we can close the gap in okra, peaches, and pumpkins!

How much less do Georgia farmers do direct sales than other states?

According to the 2007 Agricultural Census, Georgia’s direct sales accounted for 0.18 percent of their total sales. Rhode Island sold 9.5 percent of its agricultural products directly to consumers and Massachusetts sold 8.5 percent through direct sales.That looks like a potential for up to fifty times improvement.

Direct-to-consumer sales could help reverse a long-term trend, visible in recent numbers:

The most recent Agricultural Census (2007) identified nearly 48,000 farms in Georgia, a decrease of 3% from 2005. In contrast, the total dollar value of the agricultural products sold on Georgia farms increased 45% over the same period.Small farms continue to fold, leaving subdivisions and big farms. The more small farms can sell directly, the more profit they retain, and the more profitable they are, and the more likely to stay in business.

From a broader perspective, if each of the approximately 3.7 million households in the State devoted $10 per week of their total food dollars to purchasing Georgia grown productsfrom any source, not just directly from producersit could provide over $1.9 billion food dollars reinvested back into the state. This simulation allows an exploration of what a relatively small change in consumer behavior and budget can mean to the state’s economy as a whole.

That large goal requires also adding farm sales to restaurants and to supermarkets.

(Sharma and Strohbehn 2006) looked at another method of direct sales that may not be as frequently considered: restaurants or other foodservice outlets. Their analysis considered not only the costs to restaurants of buying local, but whether patrons would be willing to purchase local menu items at a slight price premium. Their findings suggest that they would be willing, and that producers can help foodservice operations promote the use of local food ingredients. Chefs of small gourmet, independently-owned restaurants are more likely to purchase local foods, with the largest obstacle to these purchases being a lack of information (Curtis and Cowee 2009).Knowing that information is critical in marketing to consumers or to foodservice outlets, the CAED interactive website known as MarketMaker ( www.marketmaker.uga.edu) and the Georgia Organics Directory ( www.georgiaorganics.org) are two resources that can help to overcome informational hurdles in selling or purchasing local food products.

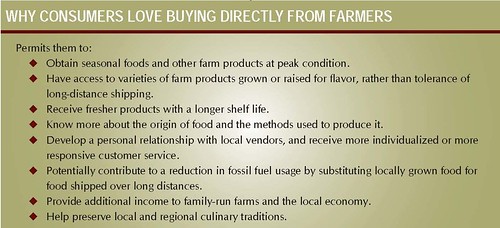

Sales from farms to supermarkets will always result in less profit to the farmer, but can still be useful for large quantities. The cost to the consumer does not have to be higher, given that local food cuts out a lot of shipping costs. Even if it is a bit higher, people may be willing to pay, because of:

the rise in consumer concerns about food safety and the source and freshness of food….Here’s where more precise food labelling would be very useful: beyond country of origin to county of origin.

Promoting local food can make a big difference to the state at large. Remember that farming is one of Georgia’s biggest industries:

Georgia’s Farm Gate Value Report for 2007 reported a direct farm gate value of $11.6 billion for food and fiber production, which resulted in a total economic impact to the state of over $58 billion.

And it’s less known that Georgia produces more diverse food crops than perhaps any other state:

This impact comes from a diverse array of commodities, of which vegetables, fruits, and nuts comprise approximately $1.1 billion of direct farm gate value, $2.85 billion in overall economic impact, and accounted for more than 25,000 jobs in 2007.

Georgia can close the gaps between production and consumption for a wide array of foods, adding another couple of billion to Georgia’s economy. And remember, local food isn’t just about money. It’s even more about providing people tastier food, supporting a diverse local economy including local farms, and improving our health.

Georgia Organics is working to help:

“These findings are some of the strongest demonstrations so far of what a small change in consumer behavior could mean for farmers, and for the entire state,” says Georgia Organics Executive Director Alice Rolls.

“More than that, I hope this study gets leaders state-wide asking why we don’t see every day foods for our Southern diets growing in the fields of Georgia.”

State-wide and right here in Lowndes County and surrounding counties.

-jsq

Short Link: